The Problem With Abundance

After decades of work, the California High-Speed Rail (CAHSR) was approved in 2008. And then everything fell apart.

The troubles began as soon as the proposition was passed. HSR officials proposed a route between San Francisco and Los Angeles that would take under 3 hours. To achieve at least 200 miles per hour, the rail needed a mostly straight track. This was a fantasy entirely ill-suited to California's terrain. To make things worse, the original price tag of $33 billion was never going to cover the cost of the rail. And topping all of this off, the proposition only allocated $10 billion, a fraction of the true cost. The approved project was nothing short of a pipe dream.

Probably the worst sin of the original project was that planners fundamentally ignored the realities of building a rail through farmland, Bay Area ecosystems, and mountains, which is what was sold to voters. This is where the California Environmental Quality Act, or CEQA, comes in. Environmental reviews take years, and a not-insignificant reason so much environmental review was even needed was because of the Pollyana endeavor. Planners didn't adequately account for the regulatory hurdles and costs, directly leading to exponential increases in time and money, as well as operating space for special interest groups. Leaders in Bay Area cities like Palo Alto and Menlo Park pushed for special considerations, and there were over 2,000 parcel claims in the Central Valley, where project construction started. The regulation, in this instance, was making sure farmers had a voice.

Time has only exacerbated these issues. The estimated price tag is now over $120 billion, with only $15 billion having been spent so far. Liberal estimates place completion in 2029. That's four times the original cost and 21 years from the passage of the original proposition.

Yet acolytes of the Abundance agenda look to CAHSR as a poster child for regulatory failure, completely sidestepping the poor planning and inadequate anticipation of regulatory process. But deregulation wouldn't have changed the reality of the route or closed the funding gap, it would have just silenced displaced communities.

The Problem With Upzoning

The Abundance agenda is a proposal to remove the burdens on modern construction to simply... create "more." More what? Well, everything. The logic goes like this: we simply need more infrastructure, more affordable housing, more public utilities, so let's cut the red tape that prevents us from making more of those things. Keen readers will have read the subtext here: it's deregulation under the guise of liberalism.

To really get into Abundance, though, we first have to talk about zoning.

Zoning is the designation of land for specific construction purposes. The zones are designated in a variety of ways, but they essentially spell out what can and cannot be built in a specific area. For example, single-family zones only permit single-family homes to be built, while multi-family zones allow for duplexes, townhomes, or apartments. You wouldn't be able to construct a 5-bedroom house on a multi-family zone, nor a condo on a single-family zone. This creates a predictable scarcity.

As a practice in the US, zoning began in the early 20th century. Ostensibly to manage urban conditions, it quickly turned into a tool of economic exclusion by keeping undesirable groups wealthier areas. New York's 1916 ordinance and Baltimore's 1910 racial zoning practices targeted low-income workers and racial minorities, all in an effort to protect property values and class segregation. Redlining punctuated this, ensuring these "undesirables" couldn't afford single-family units. And that's how we arrive at our bottleneck. Today, 75% of residential zoning is for single-family usage. As a result, there isn't enough affordable housing in the US. Being able to build that housing requires upzoning, or the redesignation of a zone into higher-density housing. This makes the Abundance solution clear: we need to upzone to be able to create affordable housing.

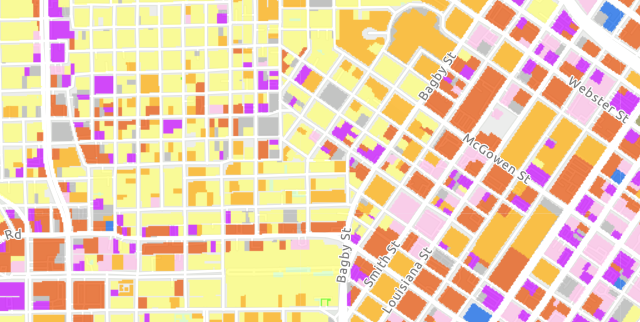

The problem is, upzoning doesn't guarantee low-income housing will be built. In Houston (which Abundance proponents will often cite as a success), most new housing units between 2015 and 2022 were unaffordable to median earners. Their lax zoning also allows for industrial facilities to be built near residential areas and schools. San Francisco was even worse – only 20% of new housing developments were for low-income following California's 2021 zoning reform. These policy changes haven't led to more low-income housing, they've created profitable high-density housing.

This is the blind spot of the Yes-In-My-Backyard (YIMBY) movement, a coalition of grassroots activists, developers, and technocrats. YIMBYism correctly identifies the most immediate and visible obstacle to upzoning: NIMBYism (Not-In-My-Backward) – or the resistance of homeowners to new development – usually to the end of preserving their investments. However, YIMBYism would identify this as a root cause, rather than a symptom of the very market interests they seek to appease. Get NIMBYism out of the way, and developers can get to building, with the market as a self-correcting force. But as we can see in Houston and San Francisco, the unchained market prioritizes profit-seeking over stewardship.

Just as the Abundance agenda's diagnosis of the high-speed rail failure ignores how regulations protect people, YIMBYism's push for bottom-up zoning reform ignores the underlying financial incentives that create our housing disparity. Upzoning is a very real solution to a very real problem, but one that only exacerbates existing conditions without strong guard rails.

What Actually Helps Renters?

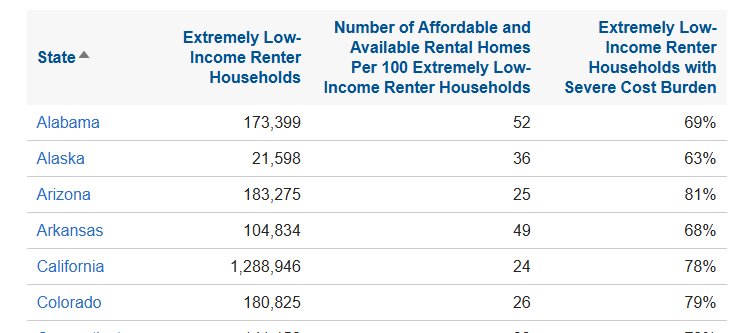

A crucial aspect of low-income housing is rentals. Currently, 34% of Americans – almost fully a third – rent their homes. Nearly half of these renters are extremely low income, meaning they either fall below the federal guideline for poverty or make less than 30% of the area median income. For every 100 extremely low income households, only 35 affordable and available rentals exist for them. This means millions of Americans spend too much of their income on rent, or live in overcrowded and undermaintained units, or even worse, face homelessness.

Renting itself doesn't just represent a financial precarity, though; it reveals the wealth extraction of the landlord class. Though many financial entities will post articles detailing how much more home ownership costs than renting, they inevitably point to buying as a benefit for both the investment opportunity and tax benefits. This is the one-two punch: the predominant narrative is that renting in cheaper, but there's always an incentive to buy. The real difference here isn't in who is paying what, but where the money goes. When you make a rent payment, that money is simply gone. It's not an investment, it doesn't provide future dividends, it is simply capital removed from the renter's existence and transferred directly to an asset portfolio. Housing costs, on the other hand, are generative. A mortgage payment isn't just evaporated funds, it is metaphorically a deposit into a savings account – complete with the opportunity to appreciate. A monthly payment for a renter is a cost, and a monthly payment for a landlord is an investment.

This isn't just the way of the world, this is the painstaking design of power relations in our access to shelter. The end result of this arrangement is the commodification of housing. It would be financially irresponsible not to treat one's property as an investment vector, and this is also what many financial institutions and advisors argue (notice how this site claims housing costs are actually cheaper). This is what undergirds the entire crisis – housing is a financial asset before it's a practical need.

So the crux of the matter is this: what policies help renters? The answer, of course, lies in the intent and the outcome. It might be helpful here to break renter policy broadly into three categories: supplementing market interests, managing market interests, and disrupting market interests.

Policies that supplement market interests are primarily rental assistance in the form of rebates or vouchers. Essentially, they either provide tax relief or direct assistance to eligible renters. While it is true that rental assistance programs can provide an immediate benefit for renters (when they're utilized), the longer-term effect is subsidizing landlords. Vouchers themselves are often refused by landlords with data suggesting refusal rates as high as 78% in some areas. Rebates are fickle, too, given that they're a form of tax relief. Tax credits are notoriously underutilized. The IRS estimates that 1 in 5 eligible households do not claim the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and this may even be worse for housing-specific rebates. Low-income renters often have severe constraints on their resources, like time or access to tax preparation. Rebates and vouchers do little to challenge commodification, and are often inaccessible.

Then we've got policies that manage market interests. These are intervening efforts, either aiming to directly influence market rates (like rent control) or punish land hoarding (vacancy taxes). This idea here is clear. There are incentives to keep raising rental prices and to hoard property. To offset the harm, then, the most immediate solutions are to control the price of rentals and to create penalties for underutilization, disincentivizing runaway commodification. Rent control can provide stability and prevent unnecessary displacement, as historically seen in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. The problem, though, is that these efforts are often neutered as to have little effect to even get them through the gate. Washington State recently passed House Bill 1217, a rent control measure capping annual increases between 7-10%. Reports from 2024, however, show that the annual rent increase in the state averages about 3%, only reaching about 5% in the highest areas. Tax vacancies are less reliable, with many landlords able to exploit loopholes – like claiming a unit is being renovated or being held for a family member – to avoid a vacancy categorization. These policies are urgent and necessary to mitigate harm to vulnerable renters, but must be comprehensive, and are not sufficient on their own.

Finally we have market disruptions: socialized housing, community land trusts, and tenant unions. These have the ultimate goal of decommodifying housing by permanently removing land from the speculative market, standardizing housing rates, and relocating power within renters. These policies correctly identify the financial incentives as the foundational obstacle to equitable housing access, and propose to offset those incentives. These also tend to be the least favorable and are often handwaved as unrealistic and, more importantly, radical.

But unrealistic and radical for whom?

It's not an accident that decommodification is so fiercely derided. It directly threatens capital, so discourse naturally collapses into accusations from the beneficiaries of capital. The entire professional-managerial class depends on property as investment, so it's only natural that home ownership is a large predictor in voting outcomes, with home owners more likely to turn out to protect their own interests. The kicker here is that we've seen the successes of social housing abroad in countries like Singapore, where 82% of citizens live in high-quality public housing. The decommodification obstacle isn't one of reality, but one of political will.

The Electoral Math of it All

So does that mean proponents of Abundance are ignorant or naive? Well, no, at least not as a rule. Where YIMBYism is the economic mechanism, Abundance is the political thesis sold in moral urgency as a strategy to create affordable housing. The core proposal is that we smartly redress outdated and ineffective regulations – like environmental reviews and zoning – to unleash developers onto the scene. But the political motivations create a different picture.

"In the American political system, to lose people is to lose power."

-Ezra Klein

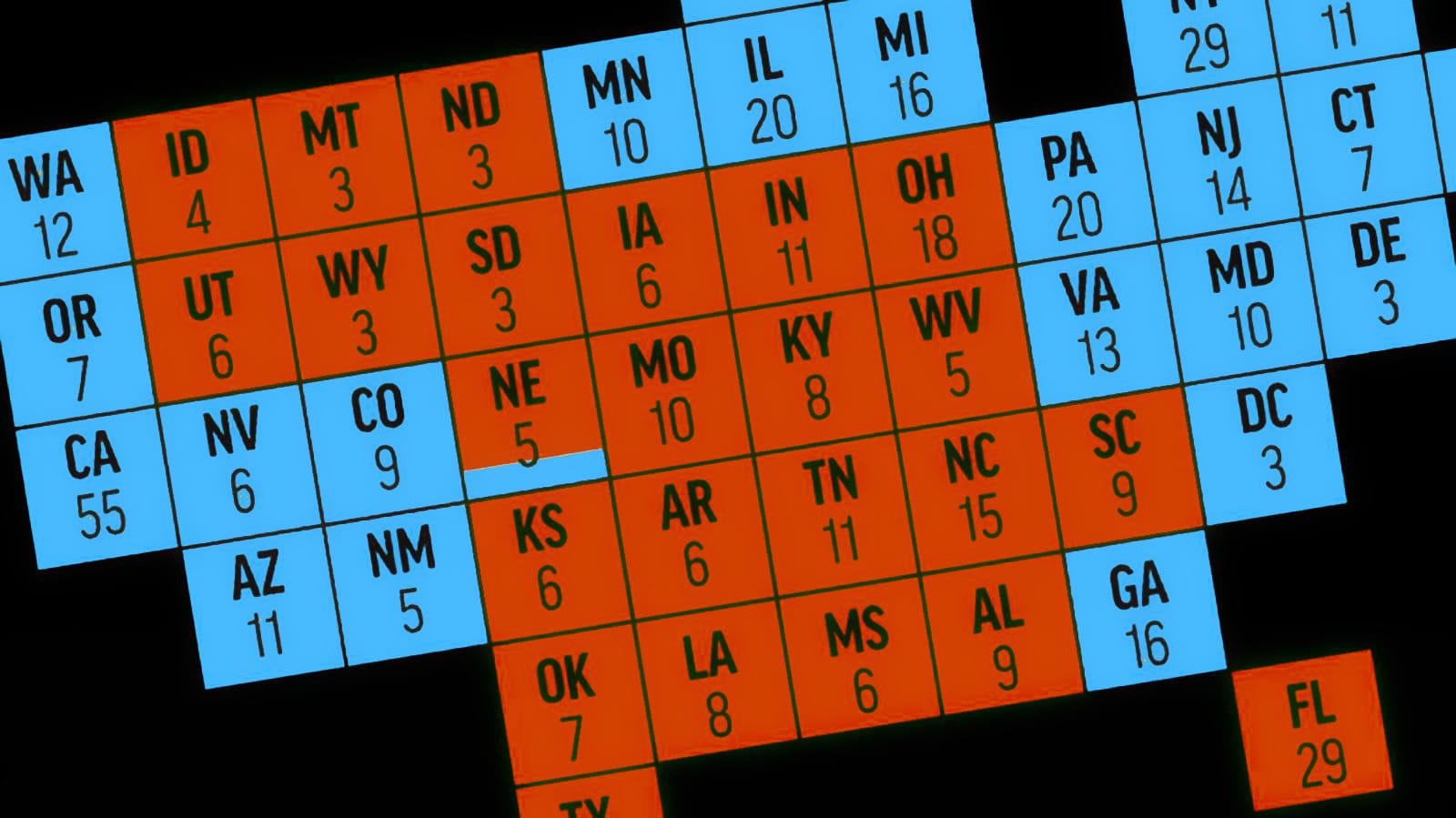

Proponent and author of Abundance, Ezra Klein, often makes his case in interviews like this: people are leaving blue states in droves, and Census projections for 2030 show Democrats losing as many as 11 seats. This migration is attributed to rising costs of living, and his proposal is that Abundance can stem (or even reverse) this trend by driving down housing costs.

This framing, however, makes the true goal obvious: retaining political power. The reason Abundance has become such a hot topic isn't in its promise to deliver on affordable housing; that's been a contested conversation for decades with no yielding on capital interests. No, it's that it promises Democrats a respite amid the recent rise in reactionary sentiment. In Ezra Klein's video, "There Is a Liberal Answer to Elon Musk," he makes the observation that, "In the American political system, to lose people is to lose power." Even the title of the video is a tell: we should be modeling our policy as a direct response to Elon Musk, instead of recognizing that his worldview, his access is that of exploitation. Klein is fundamentally disinterested in dismantling the power of capital – he wants to bend it towards liberal ends.

Klein's other common talking point in his presentations and interviews is that this migration is a bad look. Basically, Democrats look incompetent at their own stated purpose of helping the working class. In case that didn't land: we're no longer talking about the ability to materially deliver for the disenfrachised or impoverished, we're talking about the failure to maintain an image. This presents a pretty bleak rationale in the implication that meeting the working class aesthetic would absolve Democrats of improving the lives of their constituents. This isn't even the case of stated intent versus outcome, because the stated intent is the problem.

The largest condemnation of this logic, though, is the flattening of demographics. The framework of 'blue states' against 'red states' is perhaps the most dehumanizing part of electoralism, because it has no concern for the material reality of Americans. What are marginalized communities like black voters in the South, working-class organizers in rural Appalachia, or immigrants in Texas or Florida supposed to do when the proposed agenda is that of only making life better for those in so-called 'blue states'? This isn't solidarity, this is an abandonment of our most vulnerable populations in the name of retaining seats.

And yes, somewhere in this logic is the assumption that consolidating power means using that power to make everyone's lives better – Klein himself asserts as much. But this is a woefully inadequate position, particularly when examining previous Democratic administrations, who have only negotiated their political capital away for half-measures. It proposes to leave for tomorrow the problems of today. Even if Abundance could solve the housing crisis – and we have no evidence to believe it could – it does so on a dubious promise of a better life for everyone. This isn't just a strategic failure, it's a moral one.

Abundance asks the vulnerable – who only stand to lose in the face of deregulation – to wait at the back of the line while the Democratic Party tends to their most valuable electoral assets.